Father's Day 2025: When fatherhood begins in NICU – a paediatrician's story

When you work in healthcare — especially as a paediatrician — you develop a certain vocabulary for uncertainty. You learn how to hold space for anxious parents, to explain complex conditions in calm tones, and to measure your words with care. You become fluent in data, in guidelines, in clinical detachment when needed. But nothing — nothing — prepares you for the moment your own child is born prematurely.

Identity shift

My son Oscar was born at 27 weeks and 5 days. In that instant, all my professional knowledge evaporated. I wasn’t Dr Selvaratnam anymore. I was just a dad, staring at a 1kg (2lb 3oz) baby through the plastic of an incubator, trying to stay upright while the world tilted beneath me.

“I learned how quiet it can be for fathers in NICU. There’s a subtle narrative – even in healthcare – that dads are the supporters, not the ones needing support. But I was scared.”

There’s a peculiar dissonance that comes from being both a doctor and a NICU parent. Part of me recognised the machines, the sounds, the rhythm of care. I understood the acronyms on the whiteboard. I knew what a desaturation meant. But that knowledge was no comfort. In fact, sometimes it made things worse — because I could anticipate the risks too clearly. I’d seen outcomes across the spectrum, and that mental catalogue of cases became a quiet burden I couldn’t switch off.

Being Dad

People assumed I’d find it easier — that my medical background gave me an advantage. But the truth is, being a paediatrician made it harder. I didn’t want to be the clinician in the room. I wanted to be the dad. I didn’t want to calculate oxygen saturation trends or second-guess treatment plans. I wanted someone to tell me it was going to be okay.

And in the middle of all that, I learned to surrender.

Real education

The NICU was where I first held Oscar skin-to-skin against my chest, wires and tubes curled between us. It’s where I learned a new kind of medicine — not clinical, but emotional. The medicine of presence. The power of sitting beside a cot for hours, whispering love through a mask. The healing that comes not from textbooks but from tiny hands curling around your finger.

I also learned how quiet it can be for fathers in NICU. While my wife and I were both processing trauma, I found that my own fears often went unspoken. There’s a subtle narrative — even in healthcare — that dads are the supporters, not the ones needing support. But I was scared. I was frightened of each desat, each infection risk, each delay in coming off respiratory support. And I carried all that while trying to be the “strong” one.

Professionally, I’ve spent years reassuring families. But in that moment, I realised how few words can reach a parent’s heart when they’re in survival mode. The empathy I thought I understood took on a new weight. Now, when I sit with parents in my role, I know exactly how that chair feels. I know what it is to be helpless, to live scan-to-scan, and to hold on to hope like it’s oxygen.

Beginning again

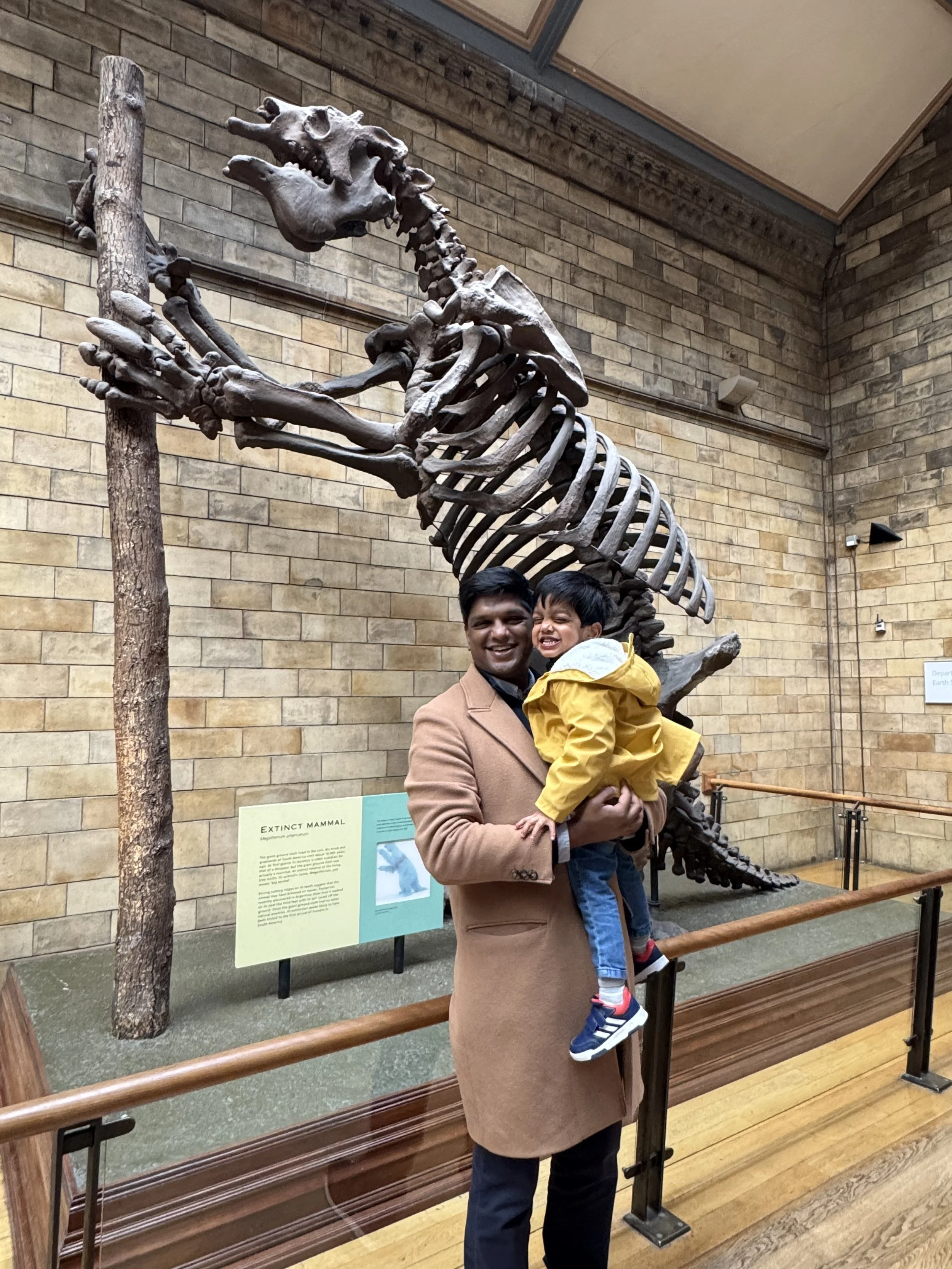

When we finally brought Oscar home, it didn’t feel like a triumphant ending. It felt like the beginning of another kind of vigilance. We’d been trained by months of alarms and observations. But over time, the NICU faded into memory. Oscar grew stronger. He started smiling, then laughing, then running. Today, he’s cheeky and brilliant and entirely himself — a walking, talking miracle of modern medicine and raw determination.

To all the NICU dads

This Father’s Day, I’m thinking about the dads who, like me, entered fatherhood not in a delivery room, but under the glow of a NICU monitor. The dads who juggle their emotions silently. The dads who sit for hours doing nothing but being there — which, as I now know, is everything.

Thanks to Edwin Selvaratnam for sharing Oscar’s story.